In order to maintain an Ironman every 4 years, I was due to race again in 2017. After the horror show of the 2013 inaugural IM Lake Tahoe I wanted a fast and flat, overcast, and fun long course that played to my strengths. I can push high watts over long, flat distances but sun glare and heat trigger migraines. I don’t shed heat fast enough to prevent shutting down. We had talked about doing a big family trip and making the race a destination vacation. Having had a great time in Paris, we wanted to go back to France. Ironman Nice would have been a beautiful course but for the past five years they’ve had record highs above 105F with a very hilly bike course. Kalmar Sweden seemed to hit all the right notes: overcast, flat, and a country we want to visit. But our third pregnancy held fast and the due date was a week after Kalmar so I withdrew. Then we found out our friends Mike and Tom were training for Ironman Canada and they had an extra room in their rental house. I signed up for the race without even looking at the course profile.

Dummy.

Ironman Canada is known for its grueling, hilly bike course.

I committed to a training plan without a coach, but one that was built for IM Canada. I shut off my coaching brain and worked the plan. One of the things I love most about Ironman training is if I trust the plan I don’t have to think about it. I put in the work and trust my body will respond with adaptation. Though I’m a member of the LATriClub, I don’t really participate in group events other than the clinic I lead for ocean swimming. (And truthfully, I’m just using the Club to get people into the clinic so I can keep doing it.) For the 16 weeks of IM training I did a few group long rides but mostly Lone Wolfed my workouts, squeezing in my training blocks before my work day or late at night after getting my kid to bed. Those nights were the hardest – falling asleep next to a warm, snuggling child only to go sit on the bike trainer for an hour, or drive to the pool and swim and run for two hours.

As the race got closer Sofia got more pregnant. The gestational diabetes was an emotional hiccup and the fatigue that came with it meant I was doing a lot more of the household and care for Aviva while also training and working. I was definitely near my breaking point of doing too much, but knowing it was all self-imposed made it feel like I had nothing to complain about. I did my work, did my workouts, got productive and efficient, and tried to lean on my contractors more to handle my workload when I couldn’t be in two places at once. Sometimes this emotional strain would result in being cranky or more curt with both family and clients, but it also pushed me to reassert boundaries that should always be there. Bedtime is bedtime, work calls after hours are an interruption and should be billed. When I’m not training I’m way more lax with letting my clients dictate my schedule. In training, it’s family and plan first, everything else after.

When I finally did look at the course map to train properly for the race I slapped myself for poor reconnaissance. The bike course has over 6000’ of climbing scattered along a non-repeating route that seemed cruel and unusual. Thankfully it was not at elevation, so altitude wouldn’t be an issue (unlike IM Lake Tahoe which started at 7,000’ and just went up up up). Nevertheless, IM Canada throws you up a long wall early in the ride and then staggers a slew of rollers until a long flat section, followed by a long climb at the end. The run course seemed forgiving, but that bike course meant I’d be heading back into the hills for long periods in the saddle on a tribike that’s not really meant to be a billy goat. My Specialized Shiv works best as a bullet train – straight line speed. I am also built for flat speed and mostly just want to die going up hills. Still, I committed and started climbing up the full stretch of Latigo, Mulholland Highway, Yerba Buena, and all the mountain passes I’d been avoiding for years in order to train my legs to enjoy the suffering. I did Palos Verdes a few times but eventually just shifted to northern routes for variety and the chance to climb all the roads I’d avoided for 10 years.

When the race day finally approached my wife was right at the point of being really done with being pregnant. Uncomfortable, slow, swollen, and unhappy. Weekly doctor appointments, four times a day blood testing for the gestational diabetes, and also trying to handle the emotional wellbeing of a five-year-old about to start kindergarten. A fine time to pack up and leave for five days on my first major race without familial support.

Having never been to Vancouver I booked an overnight stop there first, and then would drive up to Whistler to get settled into the Airbnb and start the pre-race prep. I timed it wrong and arrived in Vancouver after all the cultural locations were closed. I wound up walking several miles of the city at dusk, then got on the phone for two hours with a friend who, like many of my peers, was having a midlife crisis. (See “Be Deke”)

I wound up eating a 10pm dinner of lasagna and burned off the roof of my mouth. I was too tired and full to want to go find any single male debauchery. With a burned off soft palate and belly full of noodles I got an ice cream bar from 7-11 and called it quits for the night. I went back to my tiny, poorly air-conditioned Ramada room and slept.

The next day I packed up and stopped at the Capilano suspension bridge north of Vancouver. I walked around giant, old trees and missed my family. Being alone for long hours and feeling the creeping needles of pre-race doubts and anxiety have always been assuaged by my partner, or distracted by the needs of a small child. Having only my thoughts and questions whirling in my mind meant I could let doubt slide into my consciousness slowly. Hell, I even downloaded Headspace and tried meditation. Then, among the trees, I started getting supportive text messages from friends which really helped buoy my spirits and remind me that the days leading up to the race were the worst and once I started moving on race day that fear would go away.

The northbound drive to Whistler took about 90 minutes along a beautiful winding road bounded by mountains and water. Slowly lulled to sleep I pulled over and ate a revolting pasta dish. I rolled into Whistler early afternoon to find my friends hadn’t checked into the rental house yet. I made my way to Whistler Village and couldn’t find the Ironman village as the Olympic town was vast and meant to host ski tourists or a much bigger winter sports event. I parked and ran into Mike and Tom coming out of the parking lot. They gave me directions to the right area where I got checked in and received my packet, then was exited into the gift shop.

I’m not superstitious but I won’t buy the swag from a race unless I actually finish the damn race. There’s no guarantee I’m going to finish, even though I was confident in my ability. I still had serious concerns about the difficulty of the bike leg. I wasn’t going to spend hundreds of dollars on something I might not feel like wearing out of shame. Also, the clothing was all red and black and totally my taste except for the deal I’ve made with Sofia that I won’t wear kits that are the color of the road.

I went to Tri Bike transport and verified my bike was intact but only retrieved my gear bag. I took all my assorted crap and made it to the rental house to meet up with my friends, choose my room, and begin unpacking and staging all my stuff. I chose the bedroom off the front door with the large bunk beds but close proximity to a bathroom. The next level up was the kitchen and family room and then the bedrooms and shower on the third floor. I knew that after the race I’d want no part of those stairs, so I chose my room based solely on having less stairs to navigate for the few hours post-race before I left town Monday. I became the sullen teen off the garage with mom and dad upstairs.

I laid out all my stuff, hung my wetsuits and day clothes, and inventoried everything. Mike, Tom and I ate dinner in Whistler Village at a tourist trap and afterwards went grocery shopping to stock the kitchen with essentials. Having a house with a kitchen is the only way to travel for Ironman. Staying in a hotel gives you far less options to control your food, and dining out constantly is more expensive and rushes you through meals. People who stayed in Whistler were closer to the race village and events but we were less than a mile away and had quiet nights with control over our food.

The next day we drove back to the village, retrieved our bikes and got them to the house. Tom had the local bike techs replace his tires (more on that later) and Mike had them do a race check after transport in case anything got knocked around. We stayed lazy and restful doing very little. We met up with Mike and Tom’s friends in the TriFit group to run a small section of the beginning of the run course and keep our legs fresh. Then we sat in on the athlete briefing from 11-12 and learned that we would not be permitted to keep food overnight in our gear bags due to bears. This meant we’d have to visit our bags in T1 and T2 on race morning, adding more time to an already early wake up. A small group of us decided to drive the bike course to see what was in store.

From the car, we barely noticed the rollers heading south from Whistler to Callaghan Road. Turning right onto Callaghan begins a long, steady climb up 15 miles. It felt much like Latigo Canyon or Yerba Buena with several long stretches of climbing and some banked turns with higher degrees of ascent. It felt very challenging but not surprising. I had watched some videos discussing the bike course and every one said it was a challenge, but I also discounted these as 25% bullshit since everyone likes to say something is harder than it is for bragging rights. (All advice is 25% bullshit, 50% subjective, and 25% mildly useful.) We finally made it to the top of Callaghan and turned around at the park entrance so we wouldn’t have to pay the entry fee. We assumed there was not much more until the turnaround. (Wrong.) The descent of Callaghan would be fast and technical, then back onto the 99 Sea to Sky highway to go north, past Whistler, up to Pemberton. I noted that some sections felt like long rollers, and there were one or two hills that stood out as more than just a roller but since it was mostly straight with long bending curves it was hard to judge from the car. Pemberton is a farm town, after which is a long flat section. We looked in the sky at the mountains on either side of us and watched dozens of parachuting daredevils riding the thermals high above us. We hit the turnaround where the road literally ended in gravel, then drove back. Some of the guys fell asleep. We rounded through Pemberton and noted this was the section we were warned about. At this point we’d been driving 90 miles and were tired so we noticed it was a long drive out but had become distracted in talking or joking or just being done with driving. We got back to the house and laid low until dinner.

Saturday we rode our bikes to the village, met up with the TriFit folks again, then rode from the lake and some of the main route 99 before the big rollers. We went back to the house, packed our bike and run transition bags, stuffed them into backpacks with our wetsuits, and rode to the lake. We dropped off our bikes in transition, checked our gear bags, and then suited up for a short practice dip in the lake. At this point we noticed the warnings about “swimmer’s itch” which is a parasite in the lake that can cause a skin rash or intestinal inflammation. Everyone swore this wasn’t a big deal, but it set off our heebie jeebies. The lake swim was relaxing, even with the idea of parasites, and it was good to feel the warm lake water, 68F, and be surrounded by snowcapped mountains. Visibility was clear, though there was quite a bit of chop in the water by this point in the afternoon.

We got rinsed off, cleaned up, and took a shuttle back to the village. Then back to the house for resting and trying not to jump out of our skins. I had checked in with my family over FaceTime and text messaging but was mostly left to my own thoughts and quiet for long periods. This was a first since every major race prior I’d been with my own support squad. Still, Mike and Tom were exceptional friends and race mates and they were excited and nervous and helpful and giddy all at once. We kept each other entertained, distracted, or uplifted for what we were about to do. We had another housemate, a dietician doing his first Ironman and his delightful, pregnant wife. She cooked meals for everyone and was a giving, kind person in a house of jittery A-types (she is also an athlete and clearly knew the drill). Jeff was very focused on his race, checking in with clients racing elsewhere, and remaining pretty cool while eating his various concoctions and recipes. Meanwhile I was essentially winging my nutrition plan this time having had major gas and diarrhea issues from my thrown together food plan of stroopwaffles, Uncrustables, and Skratch labs electrolytes. My friend Eve, a dietician, correctly assessed that I was already getting a whopping dose of magnesium from my migraine prophylactics and the pectin in the jelly and magnesium in the Skratch labs were wrecking my gut. I switched to Bonk Breakers and Right Stuff and my issues went away. Still, I was eating whatever I wanted otherwise and had just eliminated roughage in the week before the race. Jeff and I were contrasts in Ironman food – him religiously disciplined and working his plan and me, yes sure I’ll eat that ice cream and brownie because oh ho ho Ironman dad bod.

Truthfully, since Vancouver I hadn’t had much of an appetite. I had cold adrenaline leaking into my system steadily as concern over my readiness and doubts of my ability seeped into my veins and conscious. I was actually eating by the clock and by force of will without tasting or enjoying much. We mostly ate chicken and mashed potatoes, or cold cut sandwiches. The night before the race we had chicken and rice cooked by the TriFit group. Protein and starch, avoiding all roughage. The twitchiness in my belly wouldn’t go away but I knew if I didn’t eat I’d be doomed so I ate as much as I could when I could. I have come to understand I really don’t like the feeling of anticipation mixed with doubt. I’m writing this race report as my wife has intermittent contractions that aren’t close enough together to mark active labor, just enough to keep us on edge. It’s the same feeling I had before racing – I’ve done this before, I know it’s going to be hard, but sitting in the limbic space between preparation and the big show itself sucks.

I got a good night’s sleep Thursday and Friday night knowing that Saturday night would be a mess. It was. Waking every hour until 3:40am when I finally just started moving to get the day going. Breakfast (oatmeal, coffee), get dressed, grab the assortment of bags with food, clothes, special needs, morning warmup clothes etc. etc. etc. and load into the car. We crammed our T2 bags with food, got body marked, and were in the shuttle by 5:20AM. Made it to the lake with plenty of time to get the bikes prepped, use the porta johns, and hydrate.

And then I’m standing in a race chute wearing a wetsuit about to do another Ironman.

I seeded myself in the 90-100 minute swim times. I figured that was what I was doing in training so that was likely where I’d be for racing. I didn’t do much speed work in the pool and never touched a track workout, so speed wasn’t going to be a factor at all in this race. I estimated my times as 90 minutes to 2 hours for the swim, 8 hours on the bike, and 5 hours for the marathon. As the sun rose and lit our surroundings I hung out with Mike and Tom, peed my wetsuit twice, and enjoyed the warm feeling on a cold morning surrounded by snowcapped mountains made for skiing. When the race played “Oh, Canada” instead of the Star-Spangled Banner many of us laughed, reminded we weren’t on home turf. A cheer, the blast of music, and then the slow shuffle of 1,000 penguins into the water. The 70.3 distance had sold out, with two thousand bikes racked in place. The full distance was less than half that. I would find out later that people are apparently intimidated by the aggressive bike course.

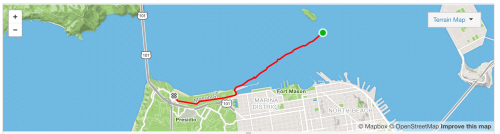

The swim is two loops around a big lake with vacation houses sprinkled around a bowl made of mountains. Green on all sides and white snow peaks. The wind was low, the chop would hit the 70.3 swimmers an hour later. Breathing and sighting were routine. Mostly it was the steady repetition of stroke and breath and finally, at long last, the settling of the heart and stomach when the action finally begins. A friend had texted me a few days back in Vancouver, “the confidence will return after the 3rd of 4th swim stroke.” He was right. Nothing settles the mind like movement – action is a cure-all. Consciousness is a curse.

I recalled that at IM Lake Tahoe I had checked my watch at the first lap and was surprised I was faster than expected. Sure enough, checked the watch at the first turn and was at 40 minutes, ahead of where I figured. The second lap I only checked my watch twice and confirmed my speed stayed consistent. It’s not fast or pretty but it gets the job done. I exited the water and checked my watch, 1:28:15 by my Garmin 1:28:16 by the timing chip. The wetsuit strippers were great, as always, and it’s one of the perks of the big races.

I admit I took some time in T1, eating a peanut butter and honey sandwich I made the day before to fuel my system while I dried off, applied sunscreen and lubricant, put on arm sleeves, calf compression, and the rest of my bike gear. I also had to load my pockets with food and I stopped again at the sunscreen table to make sure I got applied again just in case I missed a spot.

Found my bike, trotted up the hill, and mounted. My nerves had settled by this point and I had resigned myself to whatever would happen on the bike. The cutoff was 5:30PM and I had more than 8 hours to finish it, plenty of time to go slowly up those hills if I needed. More importantly, I could heed the course advice and conserve energy for the last 15 miles when I’d need it most.

I pressed start on my bike computer and it paused. Shit. Did it again, autopause. Again. Again. I’m trying to ride, focus on the course and hydration, and the goddamn thing won’t start the timer or show speed. Only watts. I reboot it, same issue. Fuck. I flip my Garmin watch around and check the time. 8:54. I give it six minutes and press start on the Garmin watch at 9AM precisely, not knowing how far I’ve gone, but only getting watts on the bike computer. Something(s) always goes wrong on an Ironman day you just have to roll with it.

Callaghan Road was just as tough as it looked on paper and from the drive. It also went on quite a while past the point where we turned off with a few more climbs until the turnaround point. Then a very fast curving descent picking up a huge amount of speed. I was still seeing other riders coming up the hill and felt ok with my pack position but was aware the strongest riders had already gone up and down while I was still climbing. They were doing their own race, I was doing my own.

Funny thing about Canada. They’re metric. Which means all the mile markers are in kilometers. My watch was showing me speed and time, and the bike computer showed watts, but I couldn’t remember if the bike was 180km or 160km. Ahhh, American exceptionalism.

I ate a Bonk Breaker on the hour and a Stroopwaffle on the half. I drank Right Stuff electrolytes in my bottles and tried to hit a bottle an hour, but it was more like a bottle every 90 minutes. Right Stuff is very, very salty and after a while it can taste harsh so I would occasionally grab a water bottle at an aid station and chug it just to get the taste of neutral water in my mouth.

The way north on 99 from Callaghan to Whistler I got merged into the 70.3 riders who had done their shorter swim and were on the course with a very short section on Callaghan Road. I ignored them as we huffed over one long roller after another. Some sections reminded me of the hills from the Alcatraz race, long hills with distant crests. These will sap your energy if you’re not careful. Finally passing Whistler, my best guess at mileage said we weren’t even halfway! And it felt like I had been in the saddle forever. I eased back a bit as we approached some aggressive “rollers” that were genuinely uphill climbs. Finally reaching Pemberton I got my special needs bag. The race announcer had suggested going to the grocery store and buying “a ton of garbage” to lift spirits. Uhh, “nothing new on race day”, buddy. I had searched for a Payday bar but they didn’t exist in Whistler, so I got a Sweet N’ Salty granola bar and a bag of beef jerky. This, along with another peanut butter and honey sandwich, a tube of chamois lube (and rubber glove to apply) and a couple Advil were in my bag. I took one bite of jerky and regretted it. I took the Advil, put on the glove and applied chamois cream as privately as possible. The granola bar had melted and was gross. I ate the sandwich as I rode away from the special needs area.

The upcoming section was where the bike leg is made or broken. It’s 30 miles out and back along a totally flat section, surrounded by farms and mountains. It feels easy going out, and if you pushed too hard to make up time for all those hills and rollers earlier, you’d be quite surprised by the headwind facing you after the turn. Earlier I had seen Manny from TriFit coming back, riding strong. After the turnaround I saw my friend Mike, about 7 miles behind me. Then a sparse number of others, and then one last guy just ahead of the LAST CAR truck slowly following. No Tom. I hoped he was OK, or maybe I had missed him. Couldn’t think about that and nothing I could do anyway.

The ride against the headwinds was showing itself in my average speed but I remember the advice – go easy on the flats because the climb back sucks.

I zipped through Pemberton, made the turn back onto 99, and then holy shit they were right.

It’s not that is just a huge, long climb. It’s not just that it was hot. It’s not just that it is 15 miles of constant uphill. Or that it happens at mile 90 after already doing a lot of climbing. It’s all of it cumulatively, everything wrapped up together. These 15 miles are what makes IM Canada cruel. It is a bike course that lays a trap for immature athletes. If you hauled ass on those flats, you will pay for it on this climb because it never, ever ends. Mentally I had to carve it up into individual sections, which I named as I climbed them, beginning with normal names like Frederick and Alexander but then rapidly devolving into “Fuck You, Billy”, “Assface McGee”, or simply, at climb 14, “COCK!”

Riders were unclipped and walking. One guy was on his back in front of a toilet. I asked if he was ok and knew his name as I slowly cruised by. He did. Still, I flagged down a race official and said, “hey, there’s a guy on his back a half mile behind me – worth checking out”. Days later I heard about a doctor doing Ironman Santa Rosa who did CPR on a dude who had a heart attack on the course and she still finished in under 16 hours. Maybe I should have stopped.

At a certain point my body didn’t want to accept solid food. I fought it as best I could but with a few miles left I also didn’t want to puke. I needed what I had to survive the run and throwing up would have serious consequences later. I kept it down but after 7.5 hours I was done eating.

The hills finally ended and I rolled into Whistler to the dismount line. I handed my bike to a kind volunteer and said “I never want to see this thing again”.

He said, “we get that a lot.”

Bike time 7:52:54.

I made it into the tent, tried to eat the peanut butter and honey sandwich from my T2 bag and realized there was nothing going in. I spit it out, got changed and put on my race kit with bottle and Bonk Breakers in the pouch, then ran out of the tent. They ran out of sunscreen. It was still bright out at nearly 5PM and would remain sunny for many more hours. Big race course fail.

My watch had been chirping LOW BATTERY the last 10 miles of the bike so I knew that if I used the GPS function I’d lose the watch. I noted that I left the tent at 4:44 and would hope to use clocks.

Except the damn course is all metric. I remembered that a marathon is 42km and change. I’d just have to get the feel for it the hard way.

I felt surprisingly good for the first few km and even caught up with Manny, who I thought was far ahead of me on the bike. He was having a hard time on the run and I slowed my race to run with him for a while. We got his heart rate down and he told me that he was doing great on the bike until he got murdered on the final 15. Wound up sitting in the T2 tent to recover and was having a hard time just moving on the run. I felt badly for him, he got sucked in by the course trap and was paying for it heavily. After some time I gradually pulled ahead and eventually saw that I was putting a lot more distance on him than I could recover without time consequences so I pushed on. When I got to an aid station I asked for broth but they told me it wasn’t coming out until 7PM. Was that a good thing? Knowing it was 5PM meant I had 7 hours to complete the marathon. Plenty of time and I was moving at a good pace. Oh, but there is a world of difference between feeling good at mile 2 or even 4 and later on at mile 18 or 22.

Still, I kept a decent pace and at aid stations I drank water, Gatorade, and stuck to liquids since my stomach was still protesting any solid food. Evidently, I had crammed enough calories in during the bike to hold me pretty well.

The run course starts in Whistler Village through a rough trail, then onto pavement jogging path, winding through a golf community and wooded lakeside cabins. It stays pretty well shaded until the big high-end golf course, and then alongside a green lake with sea planes taking off. A long stretch alongside highway 99 on one side and a lake on the other is scenic, and then a turnaround significantly further along than the 70.3 turnaround, just to give an extra kick in the pants.

I passed some people going the opposite direction, putting them around 8-10 miles ahead of me. They were hurting. A lot of walking. They were being punished for going hard on that bike course. I finally hit the first turnaround and felt like I was going to be OK. I passed Mike and gave him a hug, neither of us knew where Tom was. I passed Manny, who was still in it and fighting. His 21 year old son was doing his first Ironman and seeing him succeed, even hurting, was helping Manny push on.

IM courses that loop on themselves are a little cruel because you can just make out Mike Reilly saying “{random person’s name and city} YOU are an Ironman!” Or the variant, “you ARE an Ironman!” Or the “you are an IRON man!” You have to give Mike credit. He does a few dozen of these a year and he says his catchphrase a thousand or more times in a day. There’s only so many ways you can cook that egg. That far into a race you’re ready to be done but if it’s just your first loop you have to turn away from the sounds of cheering and raucous celebration and head back out to whatever punishment you signed up for. I mentally mapped out my landmarks and eyeballed the kilometer markers still not putting the math together. Distances stretched out. I ran for a while with a guy named Simon who was on his own fat to fit quest and after a couple miles he had just a bit more gas in the tank than I did and he moved on. I battled the war of attrition on the run until finally I was walking a lot more than I wanted. I didn’t want anything in my special needs bag and just kept going from aid station to aid station drinking water, then broth, then Gatorade, then water again.

I passed the TriFit coaches who told me Tom didn’t make the bike cutoff. I was saddened for him but needed to focus on my own race at that point. Just shutting down feelings I couldn’t use.

Eventually I was running in the dark. At one point a pair of runners took off at a bolt, and I remarked they had a lot of gas in the tank. They shouted back that they were just spectators and didn’t mean to be demoralizing. One guy yelled “soorie!” and I remarked that was my first Canadian “soorie” in 4 days. I kept up my run/walk and pushed myself as much as I could.

At some point I passed km marker 30 and realized I had about a 10K to go (and a little more). I slapped my head. A marathon is 42km. I know what a 10K feels like. I could have broken down the distance into four 10Ks and a sprint. Oh well. Math. Not something I am good at during a race. (I can edit that last sentence in half and still be right.)

I trailed a Japanese lady going into the dark final curves of the final 2 km, ignoring the “you’re almost there” yellers who really have no idea that it doesn’t help to scream that since they don’t actually tell you the distance. Someone yelled “ten more minutes!” back at km 39, and that just made no sense.

I zigged, I zagged, I saw the lights of the finish chute and a crowd of hyped people screaming – I turned on the gas and sprinted the final distance to leave every last bit of myself out there. Crossed, bent over, cried my eyes out, and was done.

Run time, 6:00:11. Six hours and eleven seconds. Eleven. Fucking. Seconds. Hugging Mike? 12 seconds. Checking on Tom’s status? Twelve seconds. Making that wrong turn in the dark? Twelve seconds. Did you know that shaving your legs can add up to FIVE WHOLE MINUTES off an Ironman bike split?!?!

So there’s that.

Total race time 15:44:23

A friend up from LA who had done the 70.3 found me and let me use her cell to call Sofia who stayed up to watch the live feed and had been tracking me obsessively all day. Talia walked me to the food table and got me hobbling towards functional. I went back to the finish line to see Mike make it in, hugging the shit out of his husband Tom, who had DNF’d.

Tom had been pulled off the course at one of the time cutoffs. He made it back to the finish line, put all of our bikes into the transport tent, retrieved all of ours transition bags, and had them tied up ready to go. Then cheered people for hours while he waited for us to finish in the dark. And he was ecstatic for us. I’ve never in my life seen someone get dealt a crushing defeat and rebound so quickly to then support others. After battling several illnesses both chronic and acute he’d had both hips replaced, gone on to do a 70.3 and had set his sights on a full. He trained his ass off for months in prep for this race. The mechanical issue was due to having the local bike mechanic replace his tires and not calibrate the brakes properly (his tires locked up on him, which has happened to me for the same reasons when I went to a Mystery Bike Shop). That’s just a reminder to never do anything new or trust a local bike shop with a mod the day before you race. But Tom acknowledged that the DNF was also because the course kicked his ass. It kicked everyone’s ass. Lots of people were walking sections of the marathon.

The key to Ironman Canada is not to underestimate the difficulty of the bike section. This was my third time at this distance. It never gets easier. However, I’ve got a much deeper understanding of the thousands of things that can happen during the race. Something will always go wrong. Something will always surprise you. Something is going to be hard you didn’t expect and something will be easy that you didn’t expect. You’ll meet incredible people all day long and everyone has an amazing story. Intentional suffering is a First World Problem and even the worst day of racing an Ironman is an opportunity to be grateful for the life and privilege you enjoy. As for that percentage breakdown of advice: YMMV (with the exception of 140.6 which I now know is 226.27377 KM).